Ancient Mathematical and Scientific Discoveries

Our ancestors weren't slouches. They cracked mathematical mysteries and built mind-bending devices that sometimes vanished from human memory, only to be reinvented millennia later.

Ever stumbled across an old photo album you forgot existed? The history of science works much the same way—buried brilliance, forgotten for centuries, then rediscovered when someone blows off the dust. Our ancestors weren't slouches. They cracked mathematical mysteries and built mind-bending devices that sometimes vanished from human memory, only to be reinvented millennia later. Talk about déjà vu on a civilization-wide scale!

Zero's Hidden Birthday Party

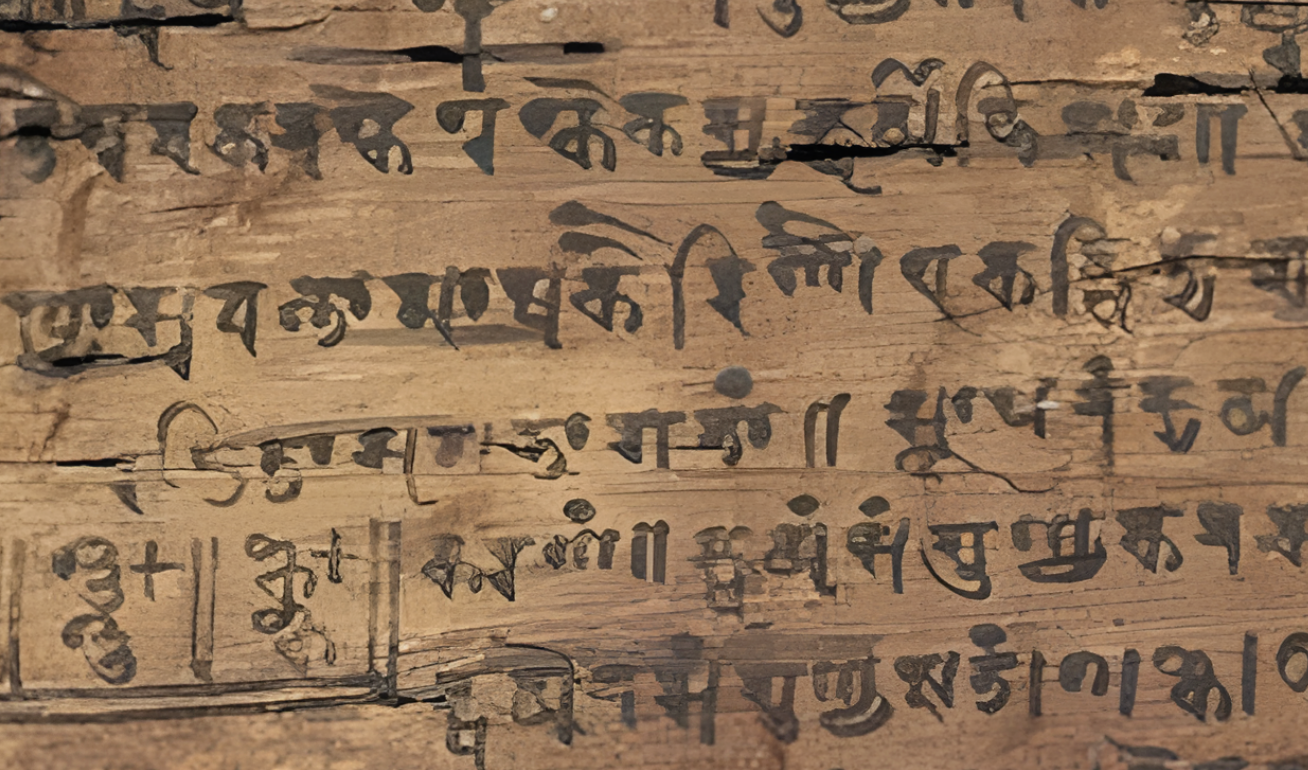

Most folks think zero showed up fashionably late to the number party. Wrong! Carbon dating just crashed zero's birthday celebration with shocking news. That dusty old Bakhshali manuscript some farmer dug up in 1881? Way older than we thought.

The math nerds at Oxford University zapped it with their fancy carbon dating gizmos and nearly fell off their chairs. Parts of that crumbly birch bark—covered in dots that worked as zeroes—date back to 224-383 CE! That's a full 500 years earlier than the previous best guess. Those dots eventually morphed into our modern-day "0" symbol. The ancient Indians were onto something huge, and nobody gave them proper credit for centuries.

Zero wasn't born overnight. It started as just a placeholder in the Gupta period (4th-6th century). By the 7th century, Indian math whizzes had promoted zero to full-number status. Brahmagupta deserves a serious high-five—his Brahmasphutasiddhanta from around 628 CE laid down the first real rules for how zero behaves. The guy even called it "sunya" (empty), a term first coined by another Indian brainiac named Pingala. Without these forgotten geniuses, your smartphone would just be a very expensive rock.

Circling Around Ellipses: The Planetary Mix-Up

Hold onto your telescopes—here's a whopper of a misconception. Hipparchus never discovered planets move in ellipses. Not even close! The ancient Greeks were completely circle-obsessed. They'd rather add circles upon circles than admit heavenly bodies might move in—gasp!—ovals.

Hipparchus cooked up mind-bendingly complex models with eccentric circles and epicycles (basically circles riding on other circles). He calculated precise mathematical ratios between these circles to explain why planets seem to wobble and occasionally backstep across the sky. Pretty ingenious stuff, but still dead wrong.

Fast-forward 1,800 years to Johannes Kepler, who finally had the guts to say, "Guys, they're just ellipses." His first law of planetary motion states that planets orbit the Sun in elliptical paths with the Sun at one focus. Revolutionary! But Kepler stood on the shoulders of giants—including Tycho Brahe, whose meticulous observations made Kepler's breakthrough possible.

Need more proof? Check out the Antikythera Mechanism. This ancient Greek contraption couldn't nail perfect accuracy because it was built on circular models! The device couldn't possibly work perfectly until after "Kepler's laws of planetary motion in 1609 and 1619" rewrote our understanding of the cosmos.

Light: Waves or Tiny Bullets?

The battle over light's true nature reads like a scientific soap opera. But here's the kicker—that drama didn't start in ancient times. The real scientific smackdown kicked off in the 18th century when Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton squared off.

Huygens bet his reputation on light traveling like ripples in a pond. Newton, stubborn as a mule, insisted light consisted of tiny particles shooting through space. Both brilliant. Both partially right. Both partially wrong. The scientific world split into camps, with each side waving their favorite genius's flag.

Then along came Thomas Young and Augustin-Jean Fresnel in the early 1800s with experiments so clever and convincing that the wave theory gained serious momentum. Young's double-slit experiment showed light creating interference patterns—something only waves should do. Case closed? Nope! It took until the 20th century and quantum mechanics for scientists to finally throw up their hands and admit light is both a wave AND a particle. How's that for a plot twist?

India's Calculus Scoop: Newton Beat by 250 Years

Here's a math bombshell for you—calculus wasn't Newton's baby. At least not first. While European mathematicians were still figuring out which end of the quill to use, the "Kerala school" in India had already cracked the code around 1350 CE. That's a 250-year head start on Newton and Leibniz!

The Kerala gang, led by mathematical rockstars Madhava and Nilakantha, nailed infinite series (calculus's secret sauce) centuries before Western mathematics caught up. They developed power series for sine, cosine, and arctangent functions that would make modern math professors whistle with appreciation.

So why don't math textbooks trumpet these names? Dr. George Gheverghese Joseph from Manchester University doesn't mince words: centuries of colonial thinking brushed non-European discoveries under the rug. The ridiculous double standard means Indian-to-European knowledge transfer needs ironclad proof, while European-to-Indian influence gets assumed without a second thought. Talk about cooking the history books!

Ancient Greece's Computer That Shouldn't Exist

In 1901, divers hauled up a corroded lump from an ancient shipwreck near Antikythera. Nobody expected to find the world's first computer. This contraption—built over 2,200 years ago—contains more gears than a Swiss watch factory.

Imagine ancient Greeks turning a hand crank to calculate astronomical positions decades in advance! This wasn't some crude sundial—we're talking about a device that tracked Olympic Games, predicted eclipses, and even modeled the moon's irregular orbit with jaw-dropping precision. Most mind-blowing? The mechanism incorporated gearing that mimicked the moon's fluctuating speed across the night sky, despite the Greeks having zero clue about elliptical orbits.

X-ray studies in 2005 finally revealed the mechanism's full complexity—dozens of interlocking bronze gears arranged with mathematical perfection. Recent research using gravity-wave astronomy techniques suggests one of its calendar rings might track a 354-day lunar calendar, though experts still argue over the details.

Here's the real kicker: nothing remotely this sophisticated appeared again until medieval clockmakers got busy over 1,000 years later. As Professor Marcus du Sautoy put it, this kind of innovation represents "one of the greatest breakthroughs" in mathematical history. Imagine if we'd lost computers for a millennium—that's essentially what happened.

Archimedes: The Original Math Punk

Archimedes wasn't just smart—he was scary smart. This Syracuse-born genius (287-212 BCE) solved problems that wouldn't be touched again until the invention of modern calculus nearly 2,000 years later. He was basically a mathematical time traveler.

His "Method of Mechanical Theorems" shows him using geometric infinitesimals to crack problems that would stump most college professors today. Take his parabola area calculation—instead of integration (which didn't exist yet), Archimedes physically balanced a parabola against a triangle on a mathematical seesaw. Crazy effective, but he considered it too unorthodox for formal proof!

The guy calculated π with ridiculous precision, invented the Archimedean spiral, and cooked up notation for numbers too big for anyone else to comprehend. His physics work was equally groundbreaking—he figured out leverage, center of gravity, and buoyancy principles that engineers still use.

And who could forget his naked "Eureka!" moment? Tasked with determining if King Hieron's crown contained sneaky silver instead of pure gold, Archimedes noticed during bath time that water displacement could measure volume. By comparing the crown's density to pure gold's known density, he could catch the cheating goldsmith. Problem solved, dignity optional.

Apollonius: Lost Works Found in Translation

Imagine finding Shakespeare's lost plays in someone's attic—that's basically what happened with Apollonius. This ancient Greek math wizard, nicknamed the "Great Geometer," wrote the definitive work on conic sections around 200 BCE. His masterpiece "Conics" explored ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas centuries before they became essential to modern science.

For ages, scholars thought only four of Apollonius's eight volumes survived the centuries. Then, historians struck gold—books five and seven turned up among 200 Arabic manuscripts gathering dust at the University of Leiden! These treasures had been sitting in plain sight since the 17th century, essentially forgotten until modern scholars recognized their importance.

Thank goodness for the Islamic Golden Age! While Europe was busy misplacing its classical knowledge, Arabic scholars were translating and preserving Greek texts like their intellectual lives depended on it. Without their careful work, these mathematical jewels would have vanished forever. This discovery proves we might have more "lost" ancient knowledge right under our noses, misfiled in some archive or tucked away in a forgotten collection.

Conclusion

History's not the neat timeline they taught you in school. It's more like your junk drawer—full of brilliance, accidents, and rediscoveries. From India's zero revolution to Greece's ancient mechanical computer, our ancestors pulled off mathematical and scientific stunts that got misplaced in history's messy filing cabinet.

Why does this matter? Because zero's journey from India to your calculator wasn't a straight line. Neither was Kerala's calculus breakthrough or the path from the Antikythera Mechanism to your laptop. Progress zigzags. Genius gets forgotten. Then someone stumbles across an old manuscript, a corroded gear, or a mathematical technique that changes everything—again.

Next time you hear about "first discoveries," remember—somebody probably thought of it earlier, wrote it down, and watched their brilliant insight vanish into history's black hole. Until some lucky archaeologist or translator blows off the dust and says, "Hey, look what I found!"